Les lieux de culte évangéliques à Bruxelles

- Auteur Barbara Menier

Un fait divers dramatique — l’effondrement du plancher d’un lieu de culte évangélique en pleine célébration pascale — entrainant la mort de deux personnes, a récemment placé sous le feu des projecteurs médiatiques la question des lieux de cultes évangéliques en région parisienne [voir notamment notre Revue de presse du 10 avril dernier]. Si les fantasmes vont bon train quant à l’existence de centaines de communautés volatiles qui pousseraient comme des champignons, leur étude reste malaisée. Les chiffres cités par le Conseil national des Evangéliques de France (CNEF) à l’occasion du drame de Stains font mention de 35 nouvelles communautés évangéliques par an pour l’ensemble de l’hexagone. Il n’en reste pas moins difficile pour ces dizaines de groupes de se trouver un lieu de culte approprié. Qu’en est-il en Région bruxelloise ?

Le déclin de la pratique religieuse en Belgique

- Auteur Caroline Sägesser

La Belgique est un pays de tradition catholique. Lors de sa constitution, plus de 99 % de sa population s’identifiaient comme tels. Depuis, cette proportion a fortement diminué, sous la double influence de la sécularisation et de l’immigration. La baisse s’est accélérée ces quarante dernières années. Sur base des derniers chiffres livrés par l’enquête décennale réalisée par une équipe de la Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KUL) et de l’Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) dans le cadre de la European Values Study, seuls 50 % des Belges se déclaraient encore catholiques en 2009. Cette estimation est probablement la plus fiable dont nous disposions (la Belgique n’organise pas de recensement des convictions religieuses) ; elle concerne une déclaration d’affiliation, qui ne donne pas de renseignements sur le degré d’adhésion à la religion catholique (dogmes et morale) ni sur la pratique religieuse. Mais en cette dernière matière, nous disposons de statistiques globalement fiables fournies par les autorités ecclésiastiques. Elles livrent des pourcentages de pratique très inférieurs à 50 %, et dont la baisse a tendance à s’accélérer.

Les enseignements de Toulouse de M. Tariq Ramadan

- Auteur Jean Philippe Schreiber

Le penseur et prédicateur musulman Tariq Ramadan a porté sur les assassinats de Toulouse et Montauban des appréciations qui ont suscité, il faut bien le dire, nombre de réactions indignées. En effet, dans l’analyse qu’a faite Tariq Ramadan des motivations du tueur, Mohamed Merah apparaît comme « un grand adolescent, un enfant, désœuvré, perdu » ; « le problème de Mohamed Merah, écrit-il, n’était ni la religion ni la politique » ; il était un « citoyen français frustré de ne pas trouver sa place, sa dignité, et le sens de la vie dans son pays ». L’explication sociale de M. Ramadan ne peut que surprendre, alors que l’auteur des tueries a lui-même justifié son action au nom d’un « djihad » islamique.

Halal et cachrout : l’économie du religieux

- Auteur Jean Philippe Schreiber

La crise économique et financière que nous connaissons a été l’occasion, en Grèce et en Italie notamment, d’ouvrir le débat sur les privilèges fiscaux dont bénéficient certaines Eglises, afin que celles-ci participent elles aussi aux efforts collectifs pour assurer la résorption des déficits publics. Ce débat a été le révélateur de deux enjeux fondamentaux : d’une part, l’important patrimoine constitué par certaines Eglises historiques, dans nombre de pays de l’Union européenne, là où les biens ecclésiastiques n’avaient pas été nationalisés sous les régimes communistes ; d’autre part, le fait que l’économie du religieux constitue depuis quelques années un élément de plus en plus pris en compte dans les études relatives au fait religieux, aux relations Eglises/Etat et à la laïcité.

Italian Church and State Ambiguities Challenged by the Debt Crisis. The ICI/IMU Affair

- Auteur Marco Ventura

Over the last years Italians have started realizing they have to pay out of their pockets for the unsustainable weight of their sick public economy, while simultaneously growing eager on asking ‘their Church,’ the Roman Catholic Church, to share the burden. The ‘ICI’ affair exposed the discontent of an upset public opinion urging the Church to stop benefiting from ingenious tax exemptions. The new government led by Mario Monti has begun shaping fairer regulations. Will he truly succeed or will the change be purely cosmetic? And will the ‘ICI’ case awake Italians, Catholics and non-Catholics alike, to the need for healthier attitudes in Italian politics and law towards the Catholic Church?

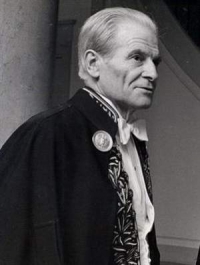

Décès de Félicien Marceau, dernier témoin du catholicisme anticonformiste de l’avant-guerre

- Auteur Cécile Vanderpelen

L’académicien Félicien Marceau, de son vrai nom Louis Carette, est mort à Paris ce mercredi 7 mars. La presse se fait l’écho de sa brillante carrière d’auteur de romans et de pièces de théâtre. Les journalistes les plus avisés rappellent qu’il fut condamné par contumace à la déchéance civile et à 15 ans de travaux forcés par l’État belge, à la Libération, pour avoir réalisé, en tant que directeur du département « Actualités » à Radio-Bruxelles (aux mains de l’occupant), des émissions aux propos ambigus. Cependant, lorsque son parcours est retracé, son engagement dans le personnalisme chrétien n’est jamais évoqué. Pourtant, non seulement il fut l’un des principaux animateurs de ce mouvement en Belgique, mais cette implication permet de mieux comprendre ses prises de position.

Le débat autour de la réaffectation des églises

- Auteur Caroline Sägesser

En Wallonie, la question de la réaffectation des églises est actuellement débattue au Parlement, à l’initiative de deux députés socialistes. Ceux-ci ont déposé une proposition visant à réaliser un cadastre des biens classés affectés à l’exercice d’un culte, première étape vers une désacralisation et une réaffectation de certains d’entre eux. Cette désacralisation est considérée comme nécessaire vu l’importance du coût de l’entretien d’édifices dont la fréquentation ne cesse de baisser. La chef du groupe PS Isabelle Simonis et le député Daniel Senesael ont déposé une proposition de décret « en vue de réaliser un cadastre des monuments classés affectés à l'exercice d'un culte ». Selon la députée, le projet est justifié par le coût élevé des travaux réalisés sur ces édifices : pour l'année 2012, sur un budget de restauration du patrimoine classé de 38 millions d'euro, 5 millions seraient exclusivement consacrés à la restauration des édifices classés ouverts au culte.

MangoGem

MangoGem