Revue de presse, 9 novembre

Haiti

"Far from B-movie cliches, vodou is spiritual system and a way of life but even in Haiti, where it became an official religion, it faces prejudice and hostility" — Vodou is elusive and endangered, but it remains the soul of Haitian people (Kim Wall and Caterina Clerici, The Guardian)

USA

"Religious groups are demanding full exemption from the requirement to provide insurance coverage of contraception under Barack Obama's healthcare law" — Supreme court to hear Christian argument for contraception exemption (Reuters, The Guardian)

En juin 2014, ORELA remettait à son commanditaire, le Centre d'Action laïque, le rapport final d'une étude réalisée par Stéphane Jonlet et consacrée aux "Dynamiques individuelles de sécularisation : le cas des personnes de tradition musulmane en Belgique". Ce rapport, rendu public depuis, a tenté d’apporter une meilleure compréhension du vécu de ceux qui, liés d’une manière ou d’une autre au « monde musulman », se sont éloignées de ses pratiques et croyances religieuses.

L’hypothèse principale qui a présidé à la conception de l’étude était celle de l’existence d’un phénomène de « double marginalisation » subi par ces personnes : d’un côté de la part de musulmans qui les rejettent en raison de la distance qu’ils affichent envers la religion ; d’un autre côté de la part d’acteurs institués de la société belge qui les assignent à une supposée identité religieuse. Le but de cette recherche a consisté à apporter un regard objectif sur ce phénomène de « double marginalisation », tout en le situant dans le contexte plus large des dynamiques de sécularisation qui se développent au sein des populations musulmanes de Belgique.

Malta: a society with values in turmoil

- Auteur Mario Vassallo

No tourist visiting Malta would nowadays repeat what a traveller to Malta, quoted by John Wignacourt in his 1914 book The Odd Man in Malta, said in 1914 — ‘Malta would have been a delightful place if every priest were a tree…’! Contemporary Malta is much greener than what it was when the Knights of St John were given the arid island in fief in 1530 AD, even though current debate often focuses on the current government’s alleged lack of concern for the environment in its drive to appease the developers. But also because the number of priests has dwindled significantly over the last half a century, and the cry of ‘Malta Kattoliċissima’ (“Malta the most Catholic”) no longer holds sway.

Revue de presse hebdo, 7 novembre

Incroyance

Publiée jeudi 5 novembre dans la revue Current Biology, une étude bat en brèche le cliché selon lequel être élevé dans un environnement religieux ferait de vous un agneau. Ce travail mené dans six Etats différents (Canada, Chine, Jordanie, Etats-Unis, Turquie et Afrique du Sud) sur 1 170 enfants de 5 à 12 ans oppose ceux élevés par une famille pratiquant un culte aux autres élevés par des familles qui s’assument comme “non religieuses”. Et pan : les chercheurs ont constaté que ces derniers seraient plus altruistes que les autres, qui présenteraient également une appétence pour l’application de châtiments plus sévères — Les enfants élevés sans religion sont plus altruistes que les autres (Théo Chapuis, Konbini)

Religious belief appears to have negative influence on children’s altruism and judgments of others’ actions even as parents see them as ‘more empathetic’ — Religious children are meaner than their secular counterparts, study finds (The Guardian)

Revue de presse, 6 novembre

Belgique

"Mgr. Jozef De Kesel sera le prochain archevêque de Malines-Bruxelles. La Libre Belgique l'a appris de bonne source jeudi après-midi : le Vatican a tranché dans le dossier de désignation du successeur de Mgr. André-Joseph Léonard. Contrairement à ce que l'on a longtemps cru, ce ne seront pas en définitive ni Mgr. Johan Bonny, l'évêque d'Anvers, ni l'abbé d'Orval, Lode Van Hecke mais bien l'actuel évêque de Bruges, Mgr. Jozef De Kesel" — Mgr Jozef De Kesel succèdera à Mgr Léonard (Christian Laporte, La Libre)

"Le mystère qui entourait ces derniers temps la nomination du successeur de Mgr André-Joseph Léonard est levé, avec l'annonce officielle du nom de son successeur. Le nouvel archevêque de Malines-Bruxelles sera Mgr Jozef De Kesel (photo), actuel évêque de Bruges. Membre de la Conférence des Evêques, il connaît la réalité bruxelloise pour y avoir exercé durant près d'une décennie" — Et le nouvel archevêque de Malines-Bruxelles est... (Angélique Tasiaux, Cathobel)

Revue de presse, 5 novembre

Belgique

"Lors des trente-cinq prochaines années, la population musulmane va croitre dans tous les pays du monde. En Belgique, elle passera de 6% à 11.8% en 2050" — 11,8 % de musulmans en Belgique en 2050 (Le Vif)

"La Foire musulmane de Bruxelles est l'une des cibles privilégiées du Vlaams Belang. Celle-ci doit se tenir, pour sa 4e édition, sur le site de Tour & Taxis du 6 au 9 novembre. Pour l'occasion, le parti d'extrême droite flamand a appelé ses sympathisants à venir manifester ce vendredi en marge de l'ouverture du salon dont le thème cette année est 'Islam et réformes'" — Pas de foire musulmane pour le Vlaams Belang (N.G., La Libre)

Revue de presse, 4 novembre

Vatican

"Deux livres qui révèlent des frasques financières. Deux arrestations dans l'entourage papal... Le pontificat de François semble être à un tournant" — Un nouveau Vatileaks ? Ce que l'on sait du scandale financier qui ébranle le Vatican (Marcelle Padovani, Libération)

"Le responsable de la Salle de Presse, le P. Federico Lombardi sj, a annoncé que deux membres de l'ancienne Commission sur l'organisation des structures économiques et administratives du Saint-Siège [...] avaient été arrêtés ce week-end par la gendarmerie vaticane. On les soupçonne d'avoir transmis des documents confidentiels à des journalistes" — Un prélat de l'Opus Dei arrêté à Rome (Christian Laporte, La Libre)

Revue de presse, 2 et 3 novembre

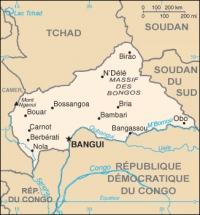

Centrafrique

"Depuis lundi 26 octobre, la capitale centrafricaine est le théâtre de nouveaux affrontements communautaires" — Violences en Centrafrique, le pape François espère maintenir son voyage (Laurent Larché, La Croix)

Tunisie

"À Sidi Lakhmi, on ne prie plus le vendredi, on dit 'dégage' au ministre des Affaires religieuses et on évince l'imam nommé par l'État" — Tunisie - Sfax : Sidi Lakhmi, la mosquée de la crispation (Benoît Delmas, Le Point)

Le synode sur la famille : la montagne qui accouche d’une souris ?

Ce 25 octobre, les 253 participants au Synode des évêques sur la famille, réunis depuis le 4 octobre, ont conclu leurs travaux et approuvé un texte élaboré par une commission de dix membres nommés par le pape. Le contenu de ce texte, publié en italien, est abondamment commenté et sera prochainement suivi de la rédaction d’une Exhortation apostolique par le pape François. Il en ressort qu’aucune modification n’a été apportée sur les questions sensibles – et attendues – que sont la place des personnes homosexuelles dans l’Église, la contraception et l’accès à la communion des divorcés remariés. On y retrouve en outre les condamnations attendues de l’« idéologie du genre », de l’avortement, de l’éducation sexuelle, du mariage entre personnes du même sexe ou encore de l’euthanasie.

Revue de presse hebdo, 31 octobre

Irlande

Le mariage homosexuel a été promulgué jeudi en Irlande, cinq mois après une consultation historique qui a vu ce pays de tradition catholique devenir la première nation au monde à l'autoriser par référendum. La présidence a annoncé cette promulgation dans un communiqué, ouvrant la voie aux premiers mariages homosexuels d'ici quelques semaines — Irlande: le mariage homosexuel promulgué (Le Figaro)

Algérie

Trois étudiants algériens de l’Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, en France, ont fait une découverte étonnante sur les thèmes de recherche faites sur Internet par les Algériens. En utilisant l’outil de Google, Google Trends, qui permet d’explorer les tendances en matière de recherches menées sur Google, ces étudiants ont constaté que les deux thèmes les plus recherchés par les Algériens sont le sexe et la religion — Les Algériens recherchent essentiellement le sexe et la religion (Abdou Semmar, Algérie Focus)

Plus...

Revue de presse, 30 octobre

Egypte

"Pour la première fois, au moins 24 chrétiens égyptiens vont être élus au Parlement grâce à un système de quotas. Une petite révolution soutenue par les Églises, qui espèrent que les chrétiens seront à terme élus sans quotas" — En Égypte, des quotas permettront à des coptes de siéger (Rémy Pigaglio, La Croix)

Centrafrique

"Les chefs religieux musulmans et chrétiens et de République centrafricaine fondent beaucoup d'espoir sur la prochaine visite du pape François dans leur pays, les 29 et 30 novembre, rapporte l'agence Apic, conscients de l'énorme tâche de réconciliation qu'ils ont à faire" — Le pape attendu par les musulman en Centrafrique (A.B., avec Apic, La Vie)

Revue de presse, 29 octobre

Arabie saoudite

"Le blogueur saoudien Raef Badaoui, emprisonné et condamné à la flagellation dans son pays pour 'insulte' envers l'islam, a obtenu jeudi le Prix Sakharov pour la liberté d'expression, décerné par le Parlement européen, selon des sources parlementaires" — Le prix Sakharov décerné au blogueur saoudien Raef Badaoui (AFP, La Libre)

Irak

"Les peshmergas, les forces armées kurdes, ont repris une trentaine de petits villages à l'ouest de Kirkouk, la grande ville pétrolière" — Irak : dans les villages repris à Daesh, l'horreur et la désolation (Ian Hamel, Le Point)

Revue de presse, 28 octobre

Arabie saoudite

"Elles estiment que les hommes avec plusieurs épouses sont incapables de les traiter de façon égale, comme indiqué dans le Coran" — Les femmes saoudiennes de plus en plus opposées à la polygamie (Oumma)

"Le blogueur saoudien Raef Badaoui pourrait subir une nouvelle séance de flagellation dans les prochains jours, a annoncé mardi son épouse Ensaf Haider, réfugiée au Canada" — Reprise de la flagellation imminente pour le blogueur saoudien Raef Badaoui (AFP, La Libre)

Revue de presse, 27 octobre

Jihadisme/Etat islamique

"L'homme d'une vingtaine d'années, qui était membre de Sharia4Belgium et avait été condamné à ce titre en février dernier devant le tribunal correctionnel d'Anvers à cinq ans de prison et 15.000 euros d'amende, a rejoint la Syrie en janvier 2013. Il s'est joint au groupe terroriste Maglis Shura Al-Mujahidin" — Le combattant belge en Syrie, Brian De Mulder, aurait été tué (Belga, La Libre)

"Sa glaçante trajectoire inquiète les services occidentaux. Comment Maxime Hauchard, jeune Normand sans envergure, a pu devenir l'un des bourreaux les plus médiatisés du groupe jihadiste État islamique (EI)?" — Jihad : Maxime Hauchard, l'itinéraire "banal" d'un Français devenu bourreau en Syrie(AFP, La Libre)

MangoGem

MangoGem